Published in Mishpacha, July 7, 2010

On April 2, 2008, Narito, Japan, suddenly exploded on the scene as a new epicenter of the Jewish universe. The news of three bochurim detained there on drugsmuggling charges was met first with incredulity, then with growing indignation, and finally unmitigated horror. In the midst of the maelstrom, dozens of courageous emissaries devoted — and continue to devote — countless hours of their time, sleepless nights, and seemingly limitless funds to the cause. Askanim, laypeople, rabbanim, and professionals rallied to help in myriad ways, living proof of the achdus and rachmanus that are hallmarks of Klal Yisrael.

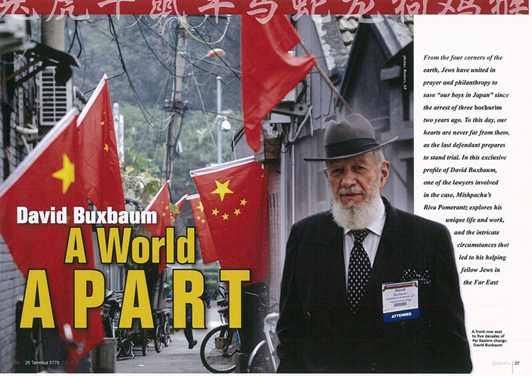

David Buxbaum is one of these heroes. Unassuming and unpretentious, this veteran lawyer emerged on the scene to help his brethren, bringing to the fore the expert knowledge of Asian law he has garnered through over fifty years of living in China and the Far East. A hefty thirteen-page résumé attests to his accomplishments and portfolio, with clients like Microsoft, Procter and Gamble, General Motors, and Kellogg's.

Yet above and beyond any prestigious client comes Buxbaum's commitment to help a fellow Yid. His counsel in the Japan case has been invaluable; his friendship, priceless. Here is a look at a man who straddles many worlds, equally comfortable in Chinese as in English, who bears personal, painful witness to an era of change that tugs at the heart and boggles the mind.

Moving East — Far East

In the beginning of David Buxbaum's story, there was darkness. The gloom cast by the dissipating smoke in the wake of World War II was even darker when viewed from the personal vantage point of a US soldier stationed in Germany during the postwar occupation. David Buxbaum felt a calling then that would pursue him forever, a whispered connection to his People that would grow and blossom through the years until his grandchildren would run through the streets of Jerusalem, peyos flying.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves. It's the late 1940s and David Buxbaum has a mission.

It isn't uncommon for a large percentage of freshly minted military discharges to vacillate about what to do after their tour of duty. Not so young Buxbaum; there was nothing ambiguous in his vision. He knew with certainty he wanted to study and practice international law, and with just as much certainty, he knew he didn't want to live in Europe, especially after what he'd seen there. So he chose a path much less traveled.

“I saw that China was becoming interesting,” he remembers. “So I went to the University of Michigan and took Asian studies, which included China, but also other aspects and interests. The natural trajectory after completing my studies would be to go to China.” He pauses. “I couldn't practice Asian law in Jerusalem!”

Fifty years is a long time by any measure, but when it comes to the life and times of China, fifty years is an eternity. When Buxbaum had his eye set on living and working in China, it was a world apart from its current incarnation today. Communist China circa 1950 was just beginning the painful business of stabilizing its economy, government, and society, and while it had made considerable progress, there was much work left to be done. Closely allied with the Soviet Union, China had not yet developed strong ties with the international community, and it was still working to rebuild the devastating blows dealt when the country was taken over by Mao Zedong's Communist forces in 1949.

“When the Communists took power, they abolished all previous laws, so now they had to start building a legal system from scratch In 1954, China enacted a constitution that may have been, even to this day, the best constitution China ever enacted,” says Buxbaum.

With its legal system just beginning to take shape, China was fertile ground for an ambitious, hard-working lawyer to set up shop. But many regarded David's dreams with hesitation.

“What did your family think of you wanting to move to the Orient?” I ask.

He laughs heartily. A nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn moving far, far East is not exactly a run-of-the-mill occurrence, especially in an era when the Far East was far from stable.

“People thought I was crazy,” he says with candid humor. There were a few professors who supported his plan, although many fellow students and faculty members discouraged him. “I was the only person — perhaps in the world, but certainly in America — who was concurrently combining Asian studies and law school,” he says, a bit ruefully. “My children were too young to have an opinion at the time; my wife was more or less supportive.”

Naysayers notwithstanding, the Buxbaum family packed their bags, with a University of Michigan law degree, a PhD, and a Harvard fellowship under David's belt, and a healthy sense of adventure.

He arrived in the Far East at the cusp of a brave new world, not quite certain of what to expect, but sure that he could make his mark. His first stint was at the University of Singapore in 1963, where he served as an exchange faculty member, and for the Buxbaums, Singapore was a lucky choice. At the time, Singapore had the only Jewish community in all of East Asia, boasting two shuls, one school, which the Buxbaum children attended, a shochet, a mohel, a mikveh, and wonderful community leaders, the Nissin family. In this vibrant setting, Yiddishkeit, Asian-style, was a real boon.

A Country in Flux

The period that preceded Buxbaum's move was one of great growth — and later, great tragedy and atrophy — in the People's Republic of China, or mainland China. The end of 1957 brought a new movement, initiated by dictator Mao Zedong, dubbed “Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom,” a daring attempt to breach the heretofore insular and almost paranoid walls of Communism. Under this initiative, divergent thoughts were encouraged; culture and academia were permitted to flourish. It was a marked contrast to the preceding years, when Mao had ruled with an iron fist, clamping down on culture, art, and commerce, even destroying historical artifacts and monuments and crushing merchants and landlords.

The Hundred Flowers Bloom initiative was experimental, to say the least, and the result — openly expressed hostility toward the autocratic nature of the Communist regime — did not please its totalitarian leader. Mao lashed out at the dissent, and in 1958 he began to close down many of China's universities, institutions, and schools.

When Mao introduced the Great Leap Forward shortly afterward, also in 1958, he apparently intended to create a new industry of iron smelting, to replace agriculture in much of the country. The plan was not what you'd call “well thought-out.”

The results were disastrous: Some estimated 40 million people died between 1958 and 1961, mostly from starvation, as they were ordered away from harvesting their crops and forced, instead, to produce steel in makeshift, backyard furnaces — without being given any iron ore! For anyone who may have wondered what, exactly, Mao was thinking, this quote from a speech he gave in 1958 may be somewhat telling: “The destruction of balance constitutes leaping forward and such destruction is better than balance. Imbalance and headache are good things,” said he. In David Buxbaum's words, “It was a cruel and vicious joke on the Chinese people.”

As the dismal state of affairs continued, regime-controlled media kept careful tabs on what was disseminated to the outside world, but they could not completely subdue reports of death and devastation. What was the international community's reaction to the goings-on? I wonder. Although he was still in graduate school during this sordid period, Buxbaum already had his finger on the pulse of his soon-tobe homeland.

“The international community didn't really realize exactly what was going on; they were ignorant,” he remembers gravely. “They knew that large numbers of people were dying of starvation, but they knew like they knew about the Jews being killed in Europe. However, it was a bloody secret that couldn't be kept; there were leaks. But the left-wing media was enthralled with Mao and his policies, just as in previous generations when people thought Lenin and Stalin were fantastic. There was hostility towards China — the Chinese were largely isolated at that time. In addition, China began to believe that they were the vanguard of socialism in the world. They began to challenge the Soviet Union [their previous ally and sponsor] and a rift opened up between China and the Soviet Union.”

Murder in the Streets

The Buxbaums arrived during this infamous era, living not in mainland China, which was not yet open freely to foreigners, but in Taiwan and then in Hong Kong, as David worked on his PhD and did some legal and academic work. But times were changing again — and they seemed to be getting even worse. After the disastrous Great Leap, Mao felt his powers slip as his failures were met with anger and rebellion. He tried to stem the tide by imposing the Cultural Revolution, which was a pleasant nom de guerre for a reign of terror.

Under this attempt to hold fast to the Maoist philosophy, counterrevolutionaries were shot in the streets, schools were shut down, and citizens were forced to chant pro-Mao slogans on penalty of their lives. The result was that China's educational, legal, and even its public transport systems, came to a grinding halt. Although at this time the Buxbaums were relatively distant from the horrible center of upheaval, they were still unwitting eyewitnesses to those turbulent times.

“Extreme leftists were acting atrociously. In China, many people were killed. Intellectuals and teachers were attacked. China was really in chaos and there was a great deal of murder, beatings, and suicide during that period. There were still forced confessions, and continuous self-criticism sessions. The Cultural Revolution was supposed to destroy the old ways and build a true socialist society, pure red, but what it did was eliminate expertise and advancement. There were no schools, there was no learning — it was unbelievable. A whole generation of Chinese lost the opportunity to have an education because of these policies.

“In Hong Kong, we experienced this. It was a terrible thing. I saw the extreme leftists surround a policeman and beat him to death. I saw them firebomb cars. There were many things I read about after seeing some of them happen myself.”

Given the gruesome and dangerous climate, did Buxbaum feel personally threatened?

“No, I really was quite safe. There were some foreigners in mainland China who were attacked, but generally speaking, the attacks and hostility were overwhelmingly directed toward the Chinese, particularly educated people and experts.”

Lifting the Chinese Curtain

Mainland China did not yet officially allow entry to Americans, and the turmoil was brutal, but Buxbaum never gave up hope; he bided his time. He felt that his ultimate goal, to establish himself as an international lawyer for foreign interests in China, was well within reach, and he was to be proven right. He watched the political machinations between China and the international community, and kept an eye on a man who was to play a big role in David Buxbaum's life, and in the course of world history — US president Richard Nixon.

“Nixon was a brilliant man. He saw the split between China and Russia as an opportunity to rearrange the power configuration of the world at that time. So he went to visit China and thus opened the door for the United States to enter into diplomatic relations with China, with the intent to counter the threat of the Soviet Union. The Chinese, who had also become hostile to the Soviet Union, were, as Nixon realized, very receptive to his overtures. After he opened the door with his diplomatic visit, three weeks later, my family and myself were able to lawfully enter China and to represent foreign businesses in mainland China. It was April 13, 1972.”

This was a personal great leap forward; a lifelong ambition for David Buxbaum would now be fulfilled. He eventually founded the first American law office on Chinese soil, and was part of the contingent that helped rebuild China's devastated legal system. But he took it slowly and carefully, first arriving alone, without his family, and then transplanting the entire Buxbaum clan to new soil.

By this time, there were winds of change sweeping through China. Perhaps the new willingness to admit Americans was a sign of this change, or perhaps it was the other way around. Either way, unprecedented opportunities were ripe for the picking. And David Buxbaum was right on board.

“In my perspective, being one of the only experts on Chinese law gave me a great opportunity to help foreigners doing business in China,” he remembers. In the stifled, repressed climate that still permeated China, change was trickling through the barriers, but there was still a long way to go.

Life in Prison

“When I came in 1972, China was a prison. Every single movement was known at any given moment. The government had communes in the countryside, street committees in the city; control was virtually absolute. Schools had been closed down, universities were shut, there were no books in bookstores, newspapers were limited. It was one big prison. The Chinese government knew everywhere you went at all times, they knew exactly what you were doing at all times. Citizens couldn't travel without permission and a formal letter from their unit. You couldn’t marry without the agreement of your unit. There was complete control of people's lives.

“A lot of people were very unhappy under this system. All intellectuals, people from a well-educated, middle-class background, who had done business previously before they were taken over by the government, were prohibited from speaking out. There were others who supported Mao. They believed in him and felt he was creating a true social revolution and pure Communism.

“I'm sure my apartment was bugged, too, but I wasn't too worried about being targeted, because I wasn't doing anything to threaten the government or the Communist Party or anyone else. Of course, because I knew people were listening, if I had something confidential to discuss with a client, I'd meet him outside the hotel.

“I was virtually singular in my position. At the time, there were no courts and no arbitration tribunals, so when we had a dispute, we brought it to the government to mediate. That was the way we did business at the time with foreigners — they signed contracts with government-controlled Chinese trading companies and the government mediated any disputes.”

No courts. No schools. No freedom of movement. Sounds pretty dreary, no? “Were you happy there?” I can't help but asking. Buxbaum's answer is thoughtful.

“I was very sympathetic to the Chinese people in light of their suffering, but I thought I saw, and in retrospect I think I'm correct, gradual change coming about — China went from being a murderous regime to being a mixed regime, a combination of Communism and capitalism. I felt it myself and I think I wasn't just seeing things. The Chinese people are very nice, welcoming, and hospitable. They're a very cultured people. This — law — was my specialty. What could I do?”

Kosher Chinese

There was plenty he could do. In addition to carving a niche for himself in the legal sense, David began by earnestly creating an infrastructure for Jewish life in China, forming a community just as he had been instrumental in doing in Hong Kong. But contrary to the popular belief that Jews and Chinese food go together like lox and bagels, keeping kosher in China was very hungry business.

“We couldn't get kosher meat at all,” he recalls. “What we had was fish, fruits, vegetables, eggs, bread we made ourselves, and that sort of thing. There were no dairy products because the Chinese barely use dairy.” Compared to the Buxbaums' lean existence in China, Singapore had been sumptuous, featuring a shochet, a shul, a rabbi, and even kosher facilities and abundant supplies, provided, in part, by Sholom Rubashkin.

In China, by contrast, religious life was basically a twice-a-year occurrence, when Jews would come to attend the Canton Fair, a center of international trade since ancient times.

“Each fair was six weeks and before and after these fairs, many people came to China in preparation of negotiating contracts. Many Jews came then and we davened together and they brought their own food. They brought dairy products and gave them to me — a real treat!”

The paucity of Jewish life had to be compensated for by trips to Israel or to Hong Kong, especially for Yamim Tovim. By the time David settled in China, his children had grown too old to attend the public schools they had previously gone to in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and were now living in New York and Israel with their grandparents, as their father shuttled back and forth regularly between continents.

Laws in Motion

But much like geological plate tectonics, China's political and social policies were shifting again. In 1978, Mao Zedong died, bringing about a change in leadership and the ascension of new people to power, namely Deng Xiaoping, Zhao Ziyang, and Hu Yaobang, who were known as enlightened reformers. This sparked the beginning of a lustrous reform period, starting with the passing of the Joint Venture Law, which permitted foreigners to invest in China, encouraging the growth of new corporations and economic entities, and also the growth of relevant bodies of law.

As these laws were enacted, lawyers like Buxbaum were challenged to learn and keep up with them. Even more invigorating, Buxbaum and others were given the privilege of having some input into certain laws as they were being drafted. The legal system and the courts were rising from the ashes, being built from their ruinous state into something stronger and more contemporary, and Buxbaum was free to join in. The courts were reestablished, long boarded-up Chinese law firms were dusted off and reopened — at first controlled by the state, then gradually becoming independent, weak as some were.

As the creaky wheels began to turn and progress slowly crept out of hiding, David describes a legal system in total chaos and disuse.

“For years, people were out of practice in law [due to the government crackdown], so many of those involved with establishing these legal practices and systems were completely ignorant. China had to create a judges law, which required judges to study law for the first time! They passed a law to require judges, prosecutors, and lawyers to take a state exam. A judge could have been a former military man, since all the authentic judges of the past were either murdered or they died of natural causes during the many years of stagnation.

“Today, a judge in China cannot become a judge unless he studies law properly. And actually, some of those original judges, who never formally studied law, turned out to be very good judges, but that's the exception.”

As law and order began to materialize, so did Buxbaum's original ambition. Now he was free to do the kind of work he had always intended to do, unencumbered by social revolution and the confines of narrow-minded Communist ideology.

“As the legal system developed and matured, our work became much more complex. Now we were dealing with real problems: contracts, intellectual property, antitrust, establishing foreign corporations, licensing.… It became a much more intricate and interesting legal system. It was a completely different world than it had been then, before the reform.”

Today, China has a different look and feel entirely. Chinese people travel abroad, go to schools of their choice, and largely do whatever they wish to without much direction or dictation by the state. Still, they do not enjoy civil liberties as we know them in the West, such as elections. It has been an incredible experience for Buxbaum to have watched this tumultuous evolution and see it come to its mostly happy conclusion. Yet, as can be expected, weaknesses still exist.

“I'd say the challenges today are weakness in the Chinese legal systems,” he says. “I do litigation as well as nonlitigation, and there are problems in the court systems of getting a just verdict, and having it enforced after a verdict is issued.”

Still, he credits the Chinese with teaching him valuable lessons: “The Chinese people are, generally speaking, very tolerant. There's no history of anti-Semitism, no social pressure to be like them.”

He also feels that living in East Asia was an impetus for spurring his growth in Yiddishkeit, simply because it was so much harder to hold his own.

“My personal Yiddishkeit has thrived. I've been very active in the development of Jewish communities, I've created some publications in Hebrew and some translations into Chinese,” says David, who reads and speaks Chinese fluently and writes, by his own wry admission, poorly. “But in terms of having chavrusas, it remains somewhat problematic!”

What influence has life in the Far East had upon Buxbaum? “I respect the Chinese people for their long history and their strong family ties, intellectual interests, strong interest in education.”

Anything else? I probe. “Well, I happen to prefer tea to coffee — and you can't get pastrami in China!” he quips.

On the Scene in Japan

When the Jewish world throbbed with the news of the arrest of the three bochurim in Japan, it was no surprise that David Buxbaum was high on the list of people to contact. It was actually one of his granddaughters in Israel who recommended that askanim contact her well-connected grandfather. Having worked in a major law firm in Japan before his eventual move to China, David was asked to help out on the case.

He quickly sprang into action, providing counsel, and arranging for competent lawyers for all three of the boys. Buxbaum laments those first critical days of the case, before the boys were indicted, when they had no lawyers. He posits that a deal might have been struck had it been organized quickly enough. In Japanese law, once a defendant is indicted, a plea deal with the prosecutor is out of the question, unlike in Israel and the United States.

He feels that although the judges were fair and competent, the guilty verdicts against two of the boys were “surprising” given the complete lack of evidence that there was intent to commit a crime.

“The decision must have been based on some feeling or some political consideration, nothing to do with the evidence,”

Buxbaum maintains. While he believes that the verdict could have been overturned upon appeal, he also acknowledges the danger in appealing, since it would mean a prolonged wait till the next trial and if, G-d forbid, the appeal were denied, the jail time would be considerably longer. “There was a feeling on my part, and also one of our lawyers, who was, herself, a former prosecutor, that an appeal would be successful. She was also shocked at the court's decision.”

Buxbaum, who attended the trial of the first boy, was equally disappointed with the verdict awarded to the second boy, who was also found guilty.

“I think the judge was more intelligent, more analytical in his decision on the second boy, but the result was equally bad. There was no criminal intent on the part of this boy.”

On a hopeful note, he adds, “Just as we were able to get the first boy back to Israel and we had wonderful cooperation with the Ministry of Justice both in Israel and Japan, along with some work of my own and our outstanding lawyers, we should be able to do the same thing for the second boy.”

From his unique vantage point, up close and personal, does he think the Japanese legal system is fair?

“I think it's very good; generally it's fair,” says Buxbaum. “I think sometimes judges make mistakes. I think the decisions in both cases were wrong. I think the publicity generated in the case had a bad effect on the boys, with people making up stories about what went on. The boys were treated reasonably fairly by Japanese standards. They were not given kosher food, that is true. I understand the Japanese authorities' concern — they don't want to treat some prisoners differently from others. However, I think the boys should have been given kosher food.”

His insider perspective also leads him to challenge certain beliefs, such as the accusation that the boys were cruelly kept in isolation.

“In order for the boys to have been allowed to mingle with other detainees, they would have had to have the uniform look of everyone else. They would have had to give up peyos and tzitzis and maintaining a kippah. That wouldn't have been a good thing. But the boys were not deliberately kept in isolation. That's not a true statement.” His hands-on involvement with the bochurim in Japan is far from Buxbaum's first foray into helping fellow Jews in distress. He has gotten involved with many Jewish prisoners in the Far East, doing whatever he can to provide them with legal counsel, expert advice, or just a friendly shalom aleichem from a landsman. Between his chesed work, he maintains a high-profile caseload with clients like Microsoft, Procter and Gamble, General Motors, and Kellogg's; a hefty thirteen-page résumé attests to his accomplishments and portfolio. Today, Buxbaum is still actively practicing law in China, though he frequently travels to the States and to his home in Neve Yaakov, Israel.

And sometimes, in the quiet of a starlit night, he wonders — and marvels — at the forces of change that conspire and confound, and the Divine Hand that ultimately guides every individual and every event, with meticulous, miraculous precision.